Bach, Multiplicity, and Interpretation

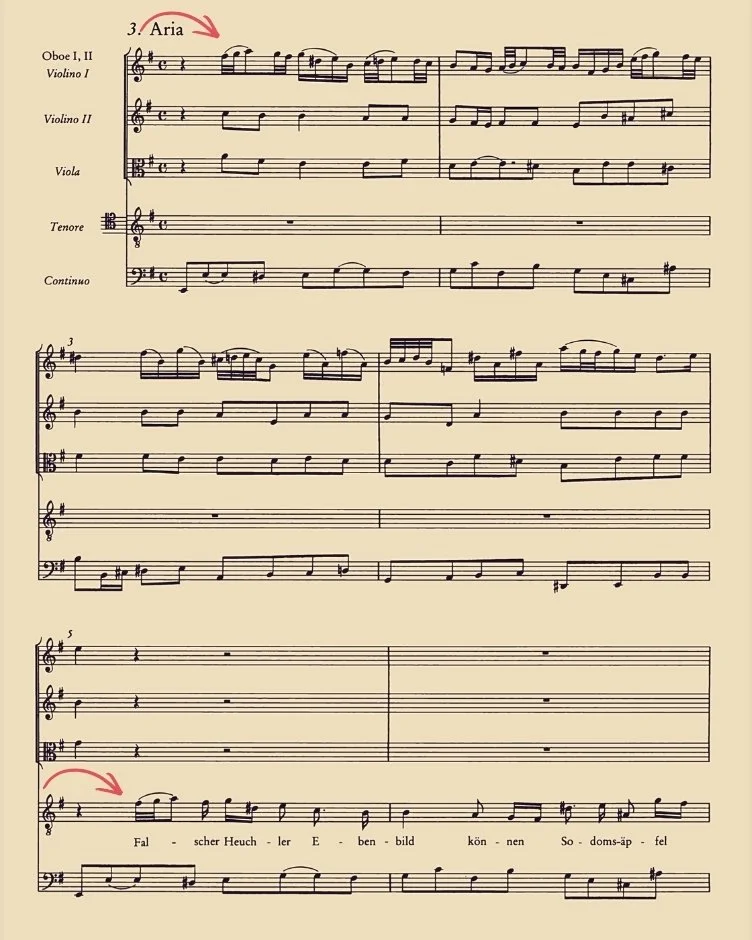

Johann Sebastian Bach: Tenor Recitative & Aria from BWV 179 Siehe zu, daß deine Gottesfurcht nicht Heuchelei sei | excerpted from Episode 13 of BACH 52 with Bach Collegium San Diego

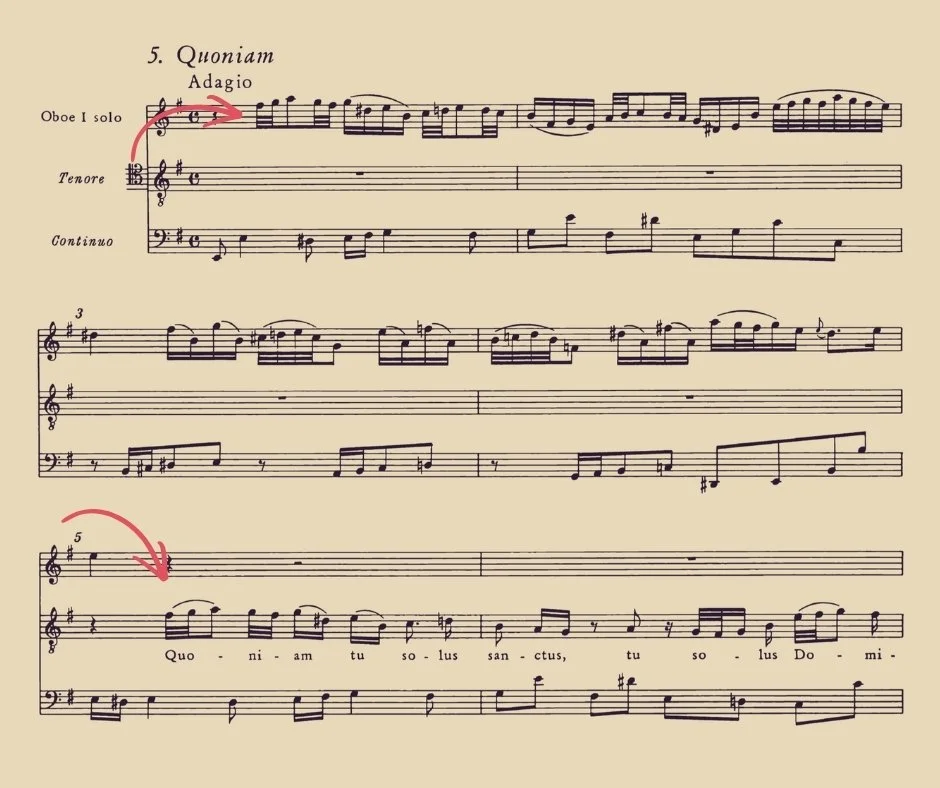

After Episode 13 of BACH 52 dropped last week, Michael Marissen wrote to remind me that the tenor aria from BWV 179 (featured at the end of the episode) resurfaces elsewhere in Bach’s output: as the Quoniam in the Mass in G Major, BWV 236. The melodic material is largely the same, and both versions feature oboe, tenor, and continuo. But in the Mass, Bach marks the aria Adagio, while in the cantata version there’s no tempo indication at all.

Quoniam from Mass in G Major, BWV 236

In addition, the cantata version sits within a much fuller orchestral fabric: strings, two oboes in unison, and the weight of a church ensemble on a Sunday morning. Even though it’s “the same” melody, the atmosphere is completely different — brisker, more animated, and, as I describe it at the end of Episode 13, almost gleeful in its condemnation.

Falscher Heuchler Ebenbild from BWV 179

In Episode 13, Michael spoke about how Bach’s music can hold a surprising spectrum of feeling at once — joy and sorrow, devotion and judgment, comfort and discomfort. Hearing these two arias side by side is another example of that same phenomenon. Nothing changes and everything changes: the same musical cell inhabits two radically different expressive worlds. The Mass leans inward and contemplative; the cantata feels outward, public, and chastising.

The idea of tempo and flexibility in Bach came up again in my earlier conversation with Jeremy Denk, who talked about the elasticity of meaning in Bach’s keyboard music. He pointed out how often Bach tells performers very little in terms of tempo or affect — and how much space that leaves for interpretation. In that interview, Jeremy even played examples from the Well-Tempered Clavier at contrasting tempi to show how the same material can read as introspective or exuberant, haunting or delightfully funny.

Quoniam from Mass in G Major, BWV 236

We notice that flexibility most easily in Bach’s instrumental music, but these two arias suggest it’s not merely incidental. Bach seems to have understood (and embraced) the fact that music could inhabit multiple emotional registers depending on tempo, scoring, and context. It’s an extraordinary demonstration of just how profoundly perspective shapes meaning, and how something that looks concrete on the page can hold more possibilities than we assume.

I was thinking about all of this while reading Michael’s email over breakfast in my hotel in Raleigh last week, where two televisions were mounted on either side of the dining room. One was tuned to CNN, analyzing cell phone video of Renee Good’s murder by an ICE agent in Minneapolis. The other was tuned to Fox News, broadcasting Kristi Noem’s account of the same incident. The footage was identical; the ticker summaries at the bottom of each screen could have been describing two entirely different events.

Thinking about Bach’s multiplicity with that horrific news cycle playing in the background as I finished my last sips of coffee, I was also reminded of something else Michael said in our interview:

“There are multiple plausible interpretations of a work of art. That's partly what makes it a work of art, right? There are multiple, but they are not infinite and they're not arbitrary. So it is actually possible to have an interpretation of something that is wrong—intellectually wrong, or even emotionally wrong…

…And that's very un-American. Because you're supposed to feel you have maximal choice, and however you feel about something — that's sort of your truth. I say, well, okay, maybe it's your truth, but that’s a weird definition of truth… There’s not only one way of looking, but there are a lot of wrong ways of looking at things.”

That distinction between multiple and infinite, between plausible and arbitrary feels crucial. In Bach, multiplicity can be generous: the same melodic idea can turn inward or outward, penitential or theatrical, depending on tempo, ensemble, and context. Even Bach seemed to acknowledge that his own perspectives on some of the material he wrote changed over the course of his life, and that he saw new possibilities in pieces he had already composed, much like we circle back to things that once felt fixed in our own lives and discover them anew with a little extra life experience. In public life, that same multiplicity can feel bewildering or dangerous. But in all these cases, we’re confronted with the fact that meaning is not singular and fixed, nor is it simply a matter of taste or preference.

Maybe part of what keeps drawing me back to Bach isn’t just the beauty of the music, but the way it insists on complexity without collapsing into relativism. It asks us to listen — not just for what we find comforting or what conforms to our already established beliefs and value systems, but for what is actually there.

You can watch the entire episode 13 of BACH 52 HERE.

BWV 179 CREDITS:

Bach Collegium San Diego | Ruben Valenzuela, director

Oboes: Kathryn Montoya, Stephen Bard

Bassoon: Anna Marsh

Violins: Elizabeth Blumenstock, Janet Straiss

Viola: Aaron Westman

Cello: Alex Greenbaum

Bass: Malachai Bandy

Theorbo: Kevin Payne

Organ: Ruben Valenzuela

VIDEO (aria, interviews, BW B-roll): Clubsoda Productions

SOUND (aria only): Daniel Rumley

Episode 13 is produced in partnership with Les Délices and Bach Collegium San Diego.

BACH 52 is made possible in part by grants from the American Bach Society, the Center for Cultural Innovation, the Bettina Baruch Foundation, and Intermusic SF.

BACH 52 is a production of Nicholas Phan Recording Projects, which is a sponsored project of Fractured Atlas, a non-profit arts service organization.

Charitable contributions in support of Nicholas Phan Recording Projects and the BACH 52 project must be made payable to “Fractured Atlas” only and are tax-deductible to the extent permitted by law..