SONGS OF THE NEW WORLD

Over the course of the next month, CAIC is broadcasting performances from the 2021 Collaborative Works Festival. This week’s broadcast is of the opening performance: CONCERT I – Songs of the New World. Below is my program note.

The chronicle of human history is riddled with tales of migration from its earliest beginnings. These are not simple stories of one group of people leaving their home for another–almost all these narratives depict unimaginable hardships at the point of origin and arduous journeys to a new promised land. These odysseys require dangerous risk and Herculean effort (see Moses’ parting of the waters of the Red Sea). Like most tales, many become embellished over time with fantastical elements, as our storytellers long for more digestible, feel-good endings, and their clarity of vision clouds over with time. Sometimes, we tell dangerously incomplete fables, like the Puritan Pilgrims escaping religious persecution who sailed to this continent only to share a Thanksgiving feast celebrating the autumnal harvest with their Native American friends.

Often, peoples setting out to migrate build unrealistic visions of the destination: a safe, welcoming, promised land, overflowing with opportunity and prosperity.The realities can be wildly different and more complex, as new lives are constructed and generations root themselves in place.

This year’s Collaborative Works Festival explores the common threads of these stories of migration through song. Tonight’s opening concert focuses on the journey itself. We examine why one might need to leave for a new home and ruminate on what happens upon arrival in the so-called promised land: do these new homes deliver on the dreams of a better life? Is there a welcome for the weary traveller?

Tonight’s program features mostly compositions by composers of the New World meditating on these questions. Interspersed with these pieces are a few songs by Franz Schubert, who also focused on various types of wanderers in his hundreds of Lieder, as well as one song by the English Renaissance composer, Thomas Campion. This peppering of songs from the distant past testifies to the timelessness of the human experience of journeying from one home to another, whether by choice or forced by necessity.

MISSY MAZZOLI:

The World Within Me is Too Small from Song from the Uproar

Missy Mazzoli’s Song from the Uproar relates the life of Isabelle Eberhardt (1877-1904), a Swiss writer and explorer who migrated to Bône, Algeria at the age of 20. Upon her arrival, Eberhardt converted to Islam, became fluent in Arabic, and began to dress as a man in order to continue exploring alone (something forbidden to Muslim women) and move about freely. Because she became so closely involved with the Arab community in Algeria and largely eschewed the European colonial community there, the French government began to suspect her of espionage. She was killed just seven years after relocating to Algeria, drowning in a flash flood at the age of 27.

Drawn to Eberhardt’s biography with its singular and unique narrative, Mazzoli’s work is part one-woman chamber opera, part song cycle. Mazzoli describes the texts composed by her and librettist Royce Vavrek as “inspired by her writing to immerse the audience in the surreal landscapes of Isabelle’s life,” and writes that she was “struck by the universal themes of her story – how much her struggles, her questions, her passions, mirrored those of women throughout the 20th and 21st century. Isabelle made a great effort to define herself as an independent woman under extreme circumstances.” The World Within Me Is Too Small relates the moment Eberhardt decides to leave Switzerland for her new home in North Africa.

RUTH CRAWFORD SEEGER: Chinaman, Laundryman

from Two Ricercari

A few years into the Great Depression, Ruth Crawford Seeger was introduced to a group in New York called the Composer’s Collective. Her husband, the composer Charles Seeger, described the aims of the group as “to connect music somehow or other with the economic situation.” Inspired by the collective’s ideal to use music in the service of movement politics, Crawford Seeger composed her Two Ricercari in 1932, taking as her texts two poems by the left-wing Chinese-American poet, Hsi Tseng Tsiang. Having immigrated to the United States through the recently established National Origins Act of 1924 quota system that enabled a very small number of migrants from China to enter as students, Tsiang went on to remain in the US, first living as a novelist and poet and left-wing activist, he would eventually act in many Hollywood movies and television shows, constantly dodging the forces of the American government and immigration authorities because of his leftist beliefs. The second of the two songs in the mini-cycle, Chinaman, Laundryman, is a setting of a poem he wrote in 1928 showing the miserable plight of a Chinese immigrant laundry worker in the United States.

Firmly established by this point in her career as one of the most preeminent composers of the American avant-garde, Crawford Seeger’s populist political leanings would soon lead her to reconsider her commitment to her serialist, ultra-modernist style, which mostly appealed to a small audience of artistic elites. Soon after the premiere of her Two Ricercari, she would devote herself to researching, transcribing, and arranging American folk music, a music she felt appealed to a broader base and was more truly “of the people”. Her shift in musical priorities would place her as the matriarchal head of a folk music dynasty that included Pete, Peggy, and Mike Seeger. Two Ricercari would be her final serialist composition in a modernist vein until her Suite for Wind Quintet, which she composed just before her premature death in 1953.

MOHAMMED FAIROUZ: Refugee Blues

In the spring of 1939, the German ship St. Louis sailed away from Europe carrying 937 German Jewish refugees fleeing the terrors of Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich, which had amped up its ethnic cleansing efforts in the wake of the horrific nation-wide Kristallnacht pogrom of the previous fall. The ship sailed first from Germany’s northern port of Hamburg to Havana, Cuba, where all but 22 of the Jewish refugees were denied entry. One additional passenger was allowed to disembark, but only because a suicide attempt necessitated his transfer to a hospital on the island. Stuck on the ship for nearly a week, the party sailed on to Miami, where the refugees hoped to be granted entry into the United States. Due to the same national quotas instituted by the 1924 immigration act that granted H.T. Tsiang entry as a student in 1926, all passengers on board were denied entry to the US. In 1939, the annual quota for immigrants coming from Germany-Austria was limited to roughly 27,000 people. All those spots had already been taken, and President Franklin D. Roosevelt, concerned about anti-war sentiment effecting his re-election prospects, neglected to take executive action to save these 911 souls. The Canadian prime minister followed suit, and after a few days, the St. Louishad no choice but to return to Europe. While some of those refugees eventually found relatively safe countries which allowed them to emigrate, roughly two-thirds of them would not be able to escape Western Europe before the Germans invaded. After two desperate trans-Atlantic journeys and multiple entreaties to various nations for safe haven, almost one-third of the refugees from the St. Louis would perish in the Holocaust.

The experience of the St. Louis refugees was fairly typical of the period, with much of the world turning a blind eye to the atrocities being committed by Hitler’s fascist regime. Taking note of these trends, W.H. Auden wrote his poem, Refugee Blues, in 1939, the same year he relocated to the United States. Writing about his draw to Auden’s poem, composer Mohammed Fairouz points out the similarities between the refugee crisis of World War II and the current plight the nearly 7 million Syrian refugees who have been forced to flee their homeland over the last decade, noting: “the words of Auden’s dark poem remain painfully relevant.”

ERROLLYN WALLEN: My Feet May Take A Little While

Errollyn Wallen’s genre-melding approach to music is reflective of her own global journey. Born in Belize, Wallen studied at the Dance Theater of Harlem in New York, after which she relocated to the United Kingdom, where she studied composition. Wallen’s song about journeying, My Feet May Take A Little While, a musical setting of her own poetry, seamlessly fuses singer-songwriter and classical modes. The result is a song that is reminiscent of an arrangement of a folk song or a spiritual from our collective consciousness, yet in reality is an original composition that is not unlike one of Schubert’s Lieder, which, at his best, have a similar effect.

IAN CUSSON: Where There’s A Wall

At the beginning of the score for his song cycle, Where There’s A Wall,composer Ian Cusson offers the following quote as an inscription: “Can we build a wall high enough around the country so as to keep out these cheaper races?” While this sounds like it might have been uttered by the 45th president of the United States, this sound byte is in fact attributed to the leading American eugenicist Charles Davenport, who wrote it more than a century ago in 1920. Cusson’s cycle is a collection of poems by the Japanese-Canadian poet, Joy Kogawa, who was interned by the Canadian government along with nearly 21,000 other Canadians of Japanese descent during World War II. Similar to the experience of Japanese-Americans during the same period following the 1941 Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor, the 6-year-old Kogawa found herself forcibly removed from her home in Vancouver, where she was born. The poems that comprise Cusson’s cycle are documents of her time in the internment camp in which she and her family were held in Slocan, British Columbia.

Cusson describes the narrative of the cycle as beginning with “a refugee invasion as seen from the perspective of the one being invaded, and who fears the coming of outsiders with their ‘feeble outstretched palms / To our apple trees and parlours.’ The work then turns to the perspective of the displaced, who, like birds, are ‘flung from our nests… and ordered to fly or die.’ There is then a song of mourning over the loss of language and the realization that this language can no longer be passed on to the next generation…The fourth song, ‘Where There’s a Wall,’ considers the many ways we can cross over walls. Barriers made to keep people out are easily breached, one of the means being through language….The cycle closes with ‘Offerings,’ which is about the ephemeral things offered to ‘us.’ (I imagine the ‘us’ in the poem refers to the interned, or, perhaps in a more contemporary context, refugees). The things offered are poor gifts, they don’t last. In the end what is left are ‘ashes’ and ‘silence.’ It is a bittersweet note to end on, perhaps one that reflects the state of the world today where internment of children happens in cages, where walls are built to keep people out, and where the fear of ‘the other’ is at an all-time high.”

NICO MUHLY: Stranger

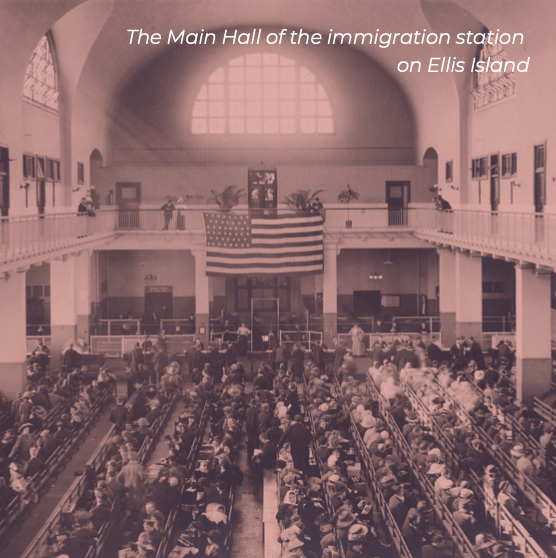

My maternal grandfather emigrated to this country sometime early in the 20th century entering through Ellis Island with the name Nicholas Assimakopoulos. He left the island, his relocation to the United States official, with a shortened name, Assimos. After some years living in America, he returned to Greece, the country where he was born, in order to find a wife so he could begin a family. Shortly after marrying my grandmother, Efrosini, he returned and they settled in Indianapolis, where he opened a diner and where my mother and aunt were born and raised.

My father, born to Chinese parents who had migrated from China to Indonesia, came to this country not long after the Immigration Act of 1965 was signed into law, our nation’s first serious attempt at righting the racist wrongs of federal Asian-exclusion policies that prevented untold numbers of Asian immigrants from coming to the United States, beginning with the Page Act of 1872, which was aimed at preventing Chinese women from immigrating to the United States.

Tonight’s program concludes with the Midwest premiere of Nico Muhly’s Stranger, a song cycle that in many ways touches on these aspects of my own immigrant family history. Preferring to set prose in lieu of poetry, Muhly weaves together musical settings of immigrant accounts of those who came through Ellis Island alongside writings protesting the United States’ Chinese Exclusion policies of the late nineteenth century. In his note for the premiere of the piece last January in Philadelphia, Muhly wrote:

“The sentiment that America is a ‘nation of immigrants,’ and the metaphor of the melting-pot can be interpreted in many ways, and too often it only practically applies to people who are perceived as white, and relates only to whatever the definition of whiteness is at the time. When I think about my own ancestors (Belorussian Jews, French, Irish, German, most arriving in the late 19th and early 20th centuries), their history over the last hundred years has mapped a kind of assimilation and clarification absolutely unavailable to people whose relatives arrived in the United States – no matter when – from China, Benin, Jamaica, or the traditional Kwakiutl land in British Columbia. These others will always face some variation of the question, ‘No, but where do you really come from?’ even if they were born in Dubuque, Providence, or Rancho Cucamonga.” Writing about his choice of texts for this piece, he writes: “These texts are not meant to address some generic sense of the American immigrant experience, but rather serve an attempt to navigate different kinds of shared American stories, from the confrontational (forced assimilation) to the practical (eye exams at the border) and make the connection between oppressive 19th-century immigration policies and those being advocated in the U.S. even now.”