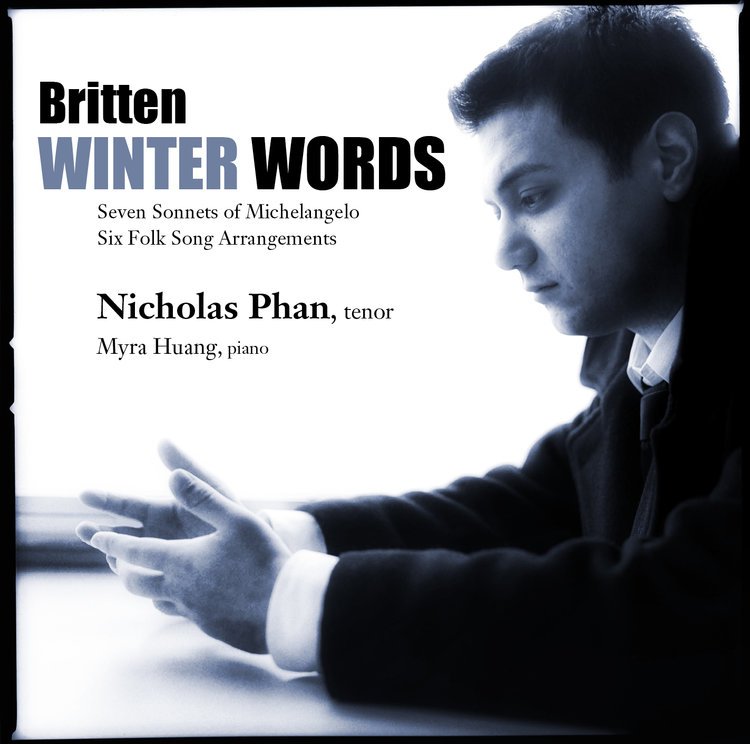

About WINTER WORDS

My youthful admiration for the music of Benjamin Britten became an obsession about five or six years ago when a pianist friend invited me to give a recital with her at a small university in Missouri, where she was teaching at the time. As we brainstormed repertoire, one of the first things she suggested that I check out was Winter Words. ‘Indulge me,’ she said. I went to the nearest library, found a score, sat down at the nearest piano and started to read through Britten’s settings of Hardy’s poems. By the time I got to ‘The Choirmaster’s Burial’, I was hooked. No matter what else we did, Winter Words had to be on the programme.

So, determined to cater for the presumed tastes of an audience in a small, middle-American town, we programmed around Winter Words, surrounding it with what we considered easy- to-swallow pieces, envisioning ourselves the equivalent of a recital-programming Mary Poppins. How wrong we were. Almost every single audience member wanted to tell us, after the recital: ‘I just loved the Britten! It was my favourite piece on the program!’ They loved Britten’s approximations of a creaking table in ‘The Old Little Table’, they found ‘Wagtail and Baby’ hilarious and slightly disturbing all at the same time, they thought ‘The Choirmaster’s Burial’ was heart-wrenchingly sweet, they adored how Britten made the piano sound like a violin in ‘At the Railway Station, Upway’, and they were heartbroken by the anguished cries of ‘How long? How long?’ at the end of the final song of the cycle, ‘Before Life and After’.

My own first impressions of Britten’s music centred on its difficulty: difficult to sing, to play, to understand. Yet as Myra and I have come to discover during our extensive explorations of Britten these past few years, his music is actually quite straightforward and packs a very passionate and primal emotional punch. His copious and detailed instructions are born of long experience as both composer and performer, as conductor and pianist, whether playing concertos, chamber music or accompanying Peter Pears. Once those markings are deciphered, the emotional core of the piece starts to shine through like a beacon. From happy to sad, bittersweet to joyful, mournful to celebratory, scornful to loving, hysterically funny to heart-wrenchingly tear-jerking, Britten’s emotional scope is incredibly broad and visceral.

Perhaps the most challenging cycle here is the Seven Sonnets of Michelangelo. The music is harmonically complex and intricate, and the vocal lines require all the technical virtuosity of any bel canto cavatina – super-seamless legato lines, an ability to float long, high phrases, the flexibility to leap smoothly from the top to the bottom of the staff. Pears himself delayed a year before performing them in public, in order to master their technical demands. Then there’s Michelangelo’s poetry, which tends to be overshadowed by his gigantic statements in visual art and sculpture when considering his artistic output, but contains no less searching, passionate philosophical meditations on the events of his life. Michelangelo began writing poetry shortly after he completed his statue of David in 1504, and while he wrote intermittently during the following quarter of a century, his most productive period as a poet was stimulated by meeting a young aristocrat, Tommaso dei Cavalieri, in 1532. Michelangelo was 57 years old, Cavalieri was 23, and did not return the older man’s passionate infatuation but remained a devoted friend; he was at Michelangelo’s bedside when he died in 1564. Of Michelangelo’s roughly 300 poems, about 50 are devoted to Cavalieri and muse on the nature of his love for him and struggle to remain within the bounds of propriety while doing so.

Britten’s music is populated with outsiders: Peter Grimes, Albert Herring and Aschenbach are just a few examples of characters on the fringe. The experience of feeling like the outsider looking in is one we have all felt at some point in our lives, and the experience of unrequited love has changed little in the 550 years since Michelangelo wrote his poetry. In setting his poems to music, Britten establishes a creative tension between the loneliness they embody and the communal experience they represent in performance. Years ago at that recital in Missouri, I felt like an outsider, worried that my musical tastes would be rejected by the community I was visiting. Yet through Britten’s music we all came together in the recital hall that night. Any differences we might have had were never even noticed, and instead we found ourselves connecting to each other through our common life experiences and made more aware of our shared humanity.